Writing a Literary Essay

| Site: | Cowichan Valley School District - Moodle |

| Course: | ELA10 - Spoken Language (2 credit), CSS, Seipp |

| Book: | Writing a Literary Essay |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 21 December 2025, 8:30 AM |

Preview: The Writing Process

This book is designed to give you information on 'Writing a Literary Essay'. Use it for reference as you progress through the course.

Literary Essay

Consider the question.

Overview:

- Learn how to write a literary essay.

- Plan your own..

- Write a first draft and get some feedback to revise your writing.

- Revise your writing.

- Submit your final draft.

Writing Targets:

Incorporated the following into your piece:

- An introduction with a thesis statement.

- Proper use of quotations.

- Properly formatted sentences.

What Makes a Good Literary Essay

This is how you will be evaluated on your writing:

The following pages will guide you in achieving these goals with outlines provided to walk you through writing your essay.

For now, just look this over to get an idea of your targets.

Planning

To start writing a Literary Essay, open this template and complete Step One: Prewriting. You can also choose one of the brainstorming, concept maps graphic organizers from the folder at the top of the course.

First choose your topic and copy and paste into Step One.

Then you will go to the next step: Writing your first draft.

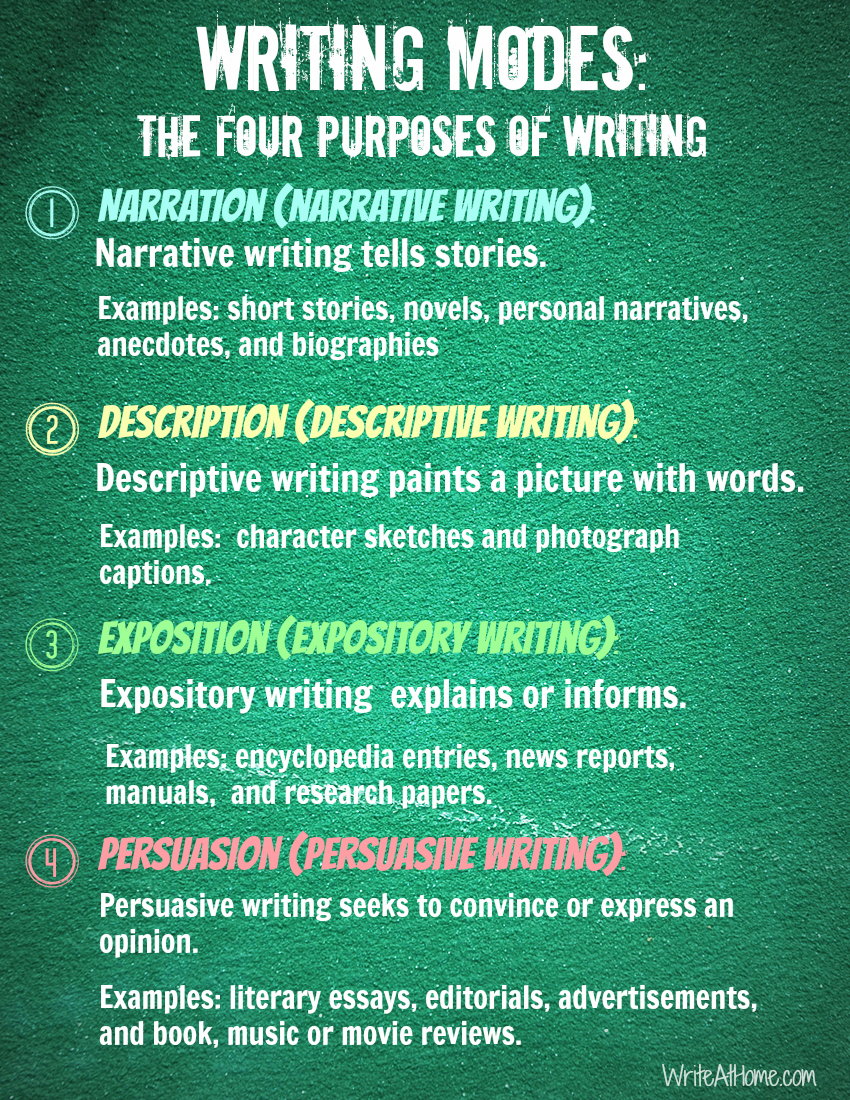

Writing modes:

Drafting

Now that your outline is complete, you can begin your draft. Don't worry about getting things perfect. You will have a chance to get some feedback and work on editing before you submit your final draft. Return to your writing template and complete step two: drafting. There are graphic organizers for this activity as well.

Revising Mini-lesson: A Good Lead

Good writers sweat their engaging beginnings. Leads give shape to the piece and to the experience of writing it. A strong engaging beginning sets the tone for the piece, determines the content and direction of the piece, and establishes the voice. Of equal importance, the engaging beginning captures the reader’s interest, inviting the reader to dive headfirst into the text.

When you read, pay attention to how the writer engages you at the beginning of a story.

When you write, experiment with multiple engaging beginnings. Deliberately craft different leads. During revision, choose the lead that you believe works best.

Revise your opening in your essay to have a compelling lead.

Below are examples of many different strategies for engaging the reader.

Typical

It was a day at the end of June. My mom, dad, brother, and I were at our camp on Rangeley Lake. We arrived the night before at 10:00, so it was dark when we got there and unpacked. We went straight to bed. The next morning, when I was eating breakfast, my dad started yelling for me from down at the dock at the top of his lungs. He said there was a car in the lake.

Some effective strategies for engaging the reader:

* Action: A Main Character Doing Something

I gulped my milk, pushed away from the table, and bolted out of the kitchen, slamming the broken screen door behind me. I ran down to our dock as fast as my legs could carry me. My feet pounded on the old wood, hurrying me toward my dad’s voice. “Scott!” he bellowed again.

“Coming, Dad!” I gasped. I couldn’t see him yet—just the sails of the boats that had already put out into the lake for the day.

* Dialogue: A Character or Characters Speaking

“Scott! Get down here on the double!” Dad bellowed. His voice sounded far away.

“Dad?” I hollered. “Where are you?” I squinted through the screen door but couldn’t see him.

“I’m down on the dock. MOVE IT. You’re not going to believe this,” he replied.

* Reaction: A Character Thinking

I couldn’t imagine why my father was hollering for me at 7:00 in the morning. I thought fast about what I might have done to get him so riled. Had he found out about the way I talked to my mother the night before, when we got to camp and she asked me to help unpack the car? Did he discover the fishing reel I broke last week? Before I could consider a third possibility, Dad’s voice shattered my thoughts.

“Scott! Move it! You’re not going to believe this!”

Additional effective strategies for engaging the reader:

* Onomatopoeia: A Sound Associated with an Action

Squish thunk, squish thunk, went out boots as we trudged down the back road of the ranch. There had been a storm the night before and as my brother, sister, and I went for a walk, we were enjoying the crisp spring air and the sunshine putting its warming hands on our backs. As we approached the corral, we noticed a mud puddle, a particularly marvelous mud puddle where the rain had mixed with water, mud, and cow dung that had been there before the storm. Little did I know that I was about to be involved in the mud fight of a lifetime.

* Shocking Statement: Something Surprising or Out of the Ordinary

They say Maniac Magee was born in a dump. They say his stomach was a cereal box and his heart a sofa spring.

They say he kept an eight-inch cockroach on a leash and that rats stood guard over him while he slept.

They say if you knew he was coming and you sprinkled salt on the ground and he ran over it, within two or three blocks, he would be as slow as everybody else.

They say…

(from Maniac Magee by Jerry Spinelli)

* List: Complex Listing of Just about Anything

Peggy was a kind woman, a quiet woman, a librarian who lived on Oak Street with her loyal dog, Ginger. They ate together. They walked together. They read books together. They watched television together. Their life was perfect.

* Lively Description: Specific Details Paint a Vivid Picture

Scarcely a breath of wind disturbed the stillness of the day, and the long rows of cabbages were bright green in the sunlight. Large white clouds drifted slowly across the deep blue sky. Now and then they obscured the sun and caused a chill on the backs of the prisoners who had to work all day long in the cabbage field.

(from “The Prisoner Who Wore Glasses” by Bessie Head)

* Question: Something to Start Readers Thinking

What’s in a name? Nothing – and everything. It is after all, just a name, one tiny piece of the puzzle that makes up a person. However, when someone has a nickname like “Dumbo,” a name can be the major force in shaping one’s sense of self. That’s how it was for me.

* Scenario: An Imaginary Situation

You’ve been drifting at sea for days with no food and no water. You have two companions. Suddenly, a half-empty bottle of water ?oats by. You ?ght over the bottle, ready to kill the others if you must in order to obtain that water. What has happened? What are you—human or animal? It is a question that H.G. Wells raises over and over in The Island of Dr. Moreau. His answer? Like it or not, we’re both.

* Quotation: Quote Someone Whose Words Encapsulate Your Theme

There are several choices for using a quote to engage the reader. One way is to begin with the quote and then tie the quote into the opening:

“The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor” ~ Aristotle

Aristotle and countless other masterful communicators have harnessed the power of metaphor to effectively persuade and inform. Metaphors allow you to make the complex simple and the controversial palatable. Conversely, metaphors allow you to create extraordinary meaning out of the seemingly mundane.

Another way is to embed the quote into your introduction:

Many of my high school friends are frustrated, and I understand that. I look around and see all kinds of problems in the world, and it doesn’t seem like anything will ever change. When I feel like that, I think about Nelson Mandela’s struggles, and I remember his claim that “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” For me, the next few years will be my chance to get an education, because I am going to change the world.

*Anecdote: A Short, Interesting Story Related to Topic

I’d been getting into a lot of trouble—failing classes, taking things that didn’t belong to me. So the guidance counselor at school suggested that my parents take me to a psychiatrist. “You mean a shrink?” my mother replied, horrified. My father and I had the same reaction. After all, what good would it do to lie on a couch while some “doctor” asked questions and took notes? So I went to my first session angry and skeptical. But after a few weeks, I realized that we had it all wrong. Those shrinks really know what they’re doing. And mine helped me turn my life around.

Revising: Personal Revision Task

Revision is where your writing is taken to the next step.

Write three different leads for your piece based on the previous lesson. Choose one to use in your piece.

Make any revisions you might want to make. This is an important part of the writing process!

Editing

Before you finish your final draft you need to edit.

You can get a parent, friend or perhaps your teacher to proofread your paper.

In any case you should check for the following:

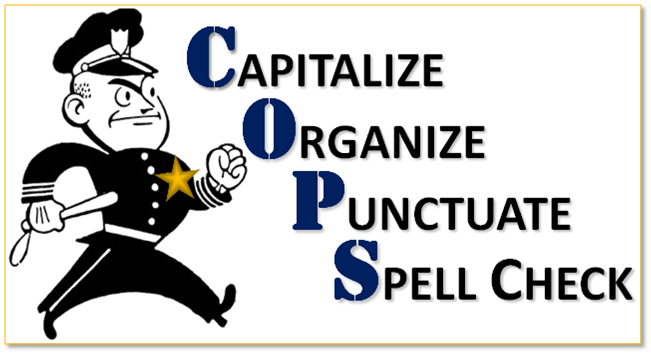

Capitalization

Organization: Paragraphs? Include a new paragraph when there is a new "scene".

Punctuation

Spelling

Publishing

Once you have:

- incorporated these ideas into your writing

- revised your first draft

- edited your work for COPS

- made sure you have included all necessary elements

... you are ready to submit your literary essay.