2.1 Read: About Nature

| Site: | Cowichan Valley School District - Moodle |

| Course: | ELA7, CSS, Sferrazza |

| Book: | 2.1 Read: About Nature |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 21 December 2025, 3:47 AM |

Introduction

We all have opinions and perspectives. How are these shaped?

Our perspectives and opinions influence how we interact with our environment and each other. It is important we take the time to understand not only how our own perspectives have been formed and communicated, but also how those of others have been because:

- exploring and sharing multiple perspectives extends our thinking.

- our cultural identity shapes our perspectives.

Throughout this unit, we will take a look at nature and how we as humans interact with it. Indigenous Peoples have always been closely in tune with the environment. The foundation of their culture is very much linked to the environment and to respect for it. View the video below on the Indigenous world view vs. the Western world view on nature.

Preview

Get ready to learn by thinking about this:

How have your views about nature been shaped by your cultural traditions and upbringing?

What experiences have shaped who you are and how you interact with nature?

Overview of Lessons:

- 1. Read/view a variety of texts about nature.

- 2. Complete the activities in the reading guide and submit.

- 3. Complete a reading project.

- 4. Take a short test to show your understanding.

- 5. In the writer's workshop, you will go through the writing project to create your own persuasive essay.

Learning Targets

Learning Targets

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- describe how understanding multiple perspectives shape our thinking.

- recognize the validity of First Peoples' oral tradition for a range of purposes.

- correctly punctuate and use conventions.

- respond and analyze different texts.

- take part in the writing process to plan, draft, and revise a persuasive piece of writing.

2.1 Legends/Stories

The Indigenous People of North America did not have scientific equipment to help them explain natural occurrences in their environment. Therefore, a story or legend would be told to help make sense of the world around them such as how the sun, moon, and stars came to be in the sky or how the salmon came to live in the river.

"Supernatural beings are prominent in many myths about the origin of places, animals, and other natural phenomena. Nanabozho is the "trickster" spirit and hero of Ojibwa mythology (part of the larger body of Anishinaabe traditional beliefs). Glooscap, a giant gifted with supernatural powers, is the hero and "transformer" of the mythology of the Wabanaki peoples. Supernatural experiences by ordinary mortals are found in other myths. For example, the Chippewa have myths explaining the first corn and the first robin, triggered by a boy's vision.[9] Some myths explain the origins of sacred rituals or objects, such as sweat lodges, wampum, and the sun dance.[10] explain an occurrence." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canadian_folklore

The Okotoks Erratic is the largest rock in the Foothills Erratic Train. The Blackfoot Legend of Napi and the Rock tells how the erratic broke in two. Read the Native American legend of Napi and the Rock as it was told to Blackfoot elder Stan Knowlton by his elders and old chiefs when he was a young boy on the Piikani Reserve in Alberta. Napi is the supernatural trickster of the Blackfoot.

After you read the legend, open your Learning Guide and complete Activity 2.1.

2.2 Natural World -Stewardship and Gratitude

The following article discusses the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the natural world. As you read it, complete the learning guide activity 2.2 found in the Learning Guide document posted at the beginning of this unit. Start to think critically about your relationship to the natural world.

Natural World

A deep and genuine relationship with the Earth has long been a central tenet of First Nations worldviews and philosophy. Long before the mainstream construct of "Mother Earth" became popular, the First Nations, Inuit, and later Metis people truly connected with the Earth as their Mother. The natural world is considered home, and the rightful stance to take upon her is a respectful, interconnected one of stewardship and gratitude.

A deep and genuine relationship with the Earth has long been a central tenet of First Nations worldviews and philosophy. Long before the mainstream construct of "Mother Earth" became popular, the First Nations, Inuit, and later Metis people truly connected with the Earth as their Mother. The natural world is considered home, and the rightful stance to take upon her is a respectful, interconnected one of stewardship and gratitude.

This relationship went further than just a powerful connection - over the millennia, First Nations and Inuit people developed intricate knowledge and understanding of the natural world. Their awareness of global laws and patterns is equal to and even exceeds mainstream scientific knowledge and offers clues to our continued survival on this planet. Their keen understanding of weather, seasons, geography, animal behaviours and patterns, plant growth, sea and water fluctuations, soil protection, gardening, ethnobotany, ecology, astronomy, and other natural knowledge is sophisticated and has been validated repeatedly over generations.

For countless generations, the First Nations and Inuit people have had unique, respectful and sacred ties to the land that sustained them. They do not claim ownership of the Earth, but rather, declare a sense of stewardship towards the land and all of its creatures. This sense of responsibility towards the land is more than a mental or even emotional obligation; it is tied intrinsically to Spirit. A strong communion with the spirit of all aspects of the earth provides a unique perceptual lens through which all activities of daily life become an expression of Spirit.

First Nations, Inuit, and Metis knowledge is strongly linked to the natural world: Indigenous languages, cultural practices, and oral traditions are all intimately connected to the Earth. Traditionally, First Nations and Inuit people see their relationship with each other and with the Earth as an interconnected web of life, which manifests as a complex ecosystem of relationships. Balance and holistic harmony are essential tenets of this knowledge and subsequent cultural practices. Embedded too is a keen belief in both adaptability and change, but change that further promotes balance and harmony, not change that creates distress, death, and the depletion of the Earth’s populations and resources. Careful observation of the seasons and the cycles of life foster an appreciation for the impermanence of things, including humans, as well as the interdependence of all life forms with each other.

A relatively recent, evolving interest in First Nations knowledge by mainstream society is both timely and to be expected. The deep sophisticated knowledge of how to live in balance with other people and all of the Earth’s inhabitants, and the very planet, herself is keenly necessary in the 21st century. Many First Nations, Inuit and Métis Elders have mused that if Western peoples had paid attention to Indigenous knowledge when they first arrived in Canada and other parts of the Americas, the current world would be much more harmonious, clean, and healthy. Now that some people are willing to listen, after decades of land mismanagement, pollution, greed, and serious depletion of animal, plant and other sources of sustenance, some keepers of Indigenous knowledge are willing to share. “One of our truths is to share. We have chosen to share our stories, our teachings, our practices, our linguistic references and maps in order that the knowledge and the wisdom that has sustained us as Coastal peoples can be understood and used by others, as we have adapted to change so must mainstream society”: (Brown & Brown, 2009, p. 6).

Article Source: https://firstnationspedagogy.ca/earth.html

2.3 Poem - Nature

H.D Carberry writes about the seasons and nature, providing yet another perspective.

Nature- Poem by H.D Carberry

We have neither Summer nor Winter

Neither Autumn nor Spring.

We have instead the days

When the gold sun shines on the lush green canefields-

Magnificently.

The days when the rain beats like bullet on the roofs

And there is no sound but thee swish of water in the gullies

And trees struggling in the high Jamaica winds.

Also there are the days when leaves fade from off guango trees’

And the reaped canefields lie bare and fallow to the sun.

But best of all there are the days when the mango and the logwood blossom

When bushes are full of the sound of bees and the scent of honey,

When the tall grass sways and shivers to the slightest breath of air,

When the buttercups have paved the earth with yellow stars

And beauty comes suddenly and the rains have gone.

After you read this poem, complete Activity 2.3 in your Learning Guide.

2.4 Informational Text: Wintertime

How do you find and use relevant evidence from a text to support an argument? Let's take a look at an informational text that discusses the many ways animals survive a harsh winter.

Click HERE to read the essay...

the Arctic Fox... and the skunk...

and the skunk...

Now open your learning guide document and complete the activity titled 2.4 Informational Writing.

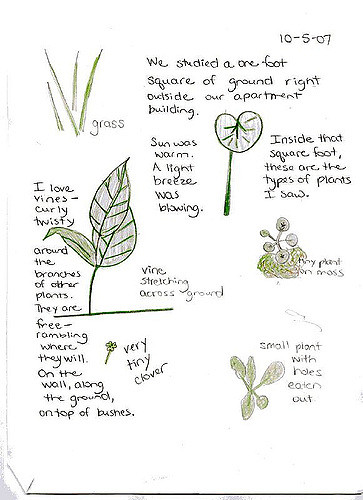

2.5 Nature Journaling

The next activity will give you a chance to connect with nature and become more aware of the places around you.

What is it?

Nature journaling is the regular recording of observations, perceptions, and feelings about the natural world around you. The recording can be done in a variety of ways, depending on your interests and purpose. Some people prefer written prose or poetry, some through drawing, painting or tape recording. There are people who record data with mathematical precision, using scientific shorthand. Many people use a combination of all these techniques.

Why do it?

“Many people keep journals to explore their own creativity and express observations and experiences of the world more fully. Some keep journals to record information and data about a place they may visit many times. They keep journals to help improve and sharpen writing skills, and in the process learn to observe better. Drawing is used as a prime record-making tool because drawing and observing are mutually reinforcing activities. With practice, it can be faster to draw a squirrel jumping from one branch to another than to write out a full description of the squirrel's actions! Working in our journals gives us a chance to slow down, reflect and focus on a place - and in the process, we establish a greater connection to the natural world. The information we collect in our journals can be used for research projects and shared with scientists and land managers that work in the areas we visit. Nature journaling helps you develop a real sense of a place and your role in that place. In our busy world, we often move quickly from place to place, without much thought or knowledge about the actual landscape we live in. Nature journaling gives us the chance to slow down and observe the world around us" Leslie & Roth, Keeping a Nature Journal

How do I do it?

|

Begin by reading this excerpt from Bev Dolittle's, The Forest Has Eyes: My thoughts fly up like birds in the sky I am free. I can fly. I go everywhere. I see everything. Towering mountain ranges And a tiny flower growing in the desert. I see cities and highways and a fallen tree. I see a grandmother telling a story to a child. I sit quietly. But my thoughts fly up like birds in the sky. Only I know where they go. |

|

Now open your learning guide document and complete the activity titled 2.5 Nature Journaling

2.6 Deeper Thinking: Sharing Stories

Most of the selections you have just read or viewed look at different perspectives on nature.

Complete the last activity in the Learning Guide, Activity 2.6, by thinking about how these shared stories have impacted your perspective on nature.

Submit your Unit 2 Learning Guide in the dropbox: Unit Two Learning Guide.

Then carry on to "Unit 2 Reading Projects".